Poetics of Clay, Colours and C(h)ords

By Waqas Manzoor

PAKISTAN PHOTO FESTIVAL FELLOWSHIP 2021 PROJECT

Hand-making toys is a visual art, this project intended to dive into the visual language of toy-making, by uncovering individual symbolisms, motivations, and their interconnections in the toymaker’s life on both a personal and professional level.

I was lying in my room on a sunny morning when I heard the sound of Rehrhi, (tuk, tuk tuk…) The sound came from the drum cart, and it brought back many pleasant childhood memories that had been long lost. I rushed towards the toy seller who was carrying these toys; Rehrhi and Damru, rattle in a wooden basket on his head. After inquiring about the price, I bought some toys and asked about the location of his house. He did not have a mobile phone and just tried to explain the locality of his house to me. The quest of undertaking a project on these folk toys began with this event.

When I started working on this project and tried to find these toymakers, it took me a while to trace their localities from Thokar Niaz Baig surroundings to the banks of river Ravi, but I could not find these toymakers until I found a family of toymakers in Shahdara, Lahore. When I paid a visit to these toy makers and found a few tent houses in a empty plot among the high cemented houses. I went to one of the houses after asking permission and but they looked at me suspiciously and later, while in a conversation, discovered that they thought I may be a LDA representative who had come to make them vacate the plot. Some of the family members were already making the toys and a woman in her sixties was supervising them. I told them that I wanted to document these toys and they agreed. One of the young toy makers also gave me his mobile number and asked me to visit them after a week. I called this toy maker, Mohsin Abbas a day before the agreed time and he broke the news that,” Please don’t come we have shifted to our village back in Sargodha and there is no more making toys in Lahore.” The pho call left me in shock and silence…

The struggle to find these folk toymakers began again and it ended while I was strolling at Babu Sabu that I found a tent house and these captivating folk toys were falling out from the tent house and I could see it from a long distance.

My project revolves around photographing the consumer network – the relations between toy-users and toys and how values of play have been changed by the transformation of toys. This project examines the ways in which the toys and the environment, culture and social life are inter-connected – something that is lost with the arrival and growing popularity of imported, digital corporate toys and electronic games. The project draws our attention to the ways in which life, living and the environment work together as initially toys were made of organic material (clay, paper, cardboard, bamboo sticks, strings, and rubber bands) that is beautifully recycled by these creative and inventive craftspeople for making toys as compared to modern toys made by plastic-based material.

Finally, I examined how handcrafts toy-maker communities are struggling in urban settings and what role changing trends have to play as per market demand and the global economy. How self-employed traditional craftsmanship is struggling in the face of a more advanced global industry.

Hand-making toys is a visual art, this project intended to dive into the visual language of toy-making, by uncovering individual symbolisms, motivations, and their interconnections in the toymaker’s life on both a personal and professional level.

I was drawn to this project because hand-made toys have started vanishing from our neighborhood as they used to bring festivity to children. With the prevalent globalization and massive technological advancement in recent years many local indigenous crafts have been extinct i.e., we no more witness street jugglers and puppeteers on the streets and many are endangered. If we pay attention, all activities were also linked to the rich culture of celebrating carnivals (social celebrations) in subcontinent the tradition is also disappearing lately. I felt a dire need to document this artistic inheritance that is on the verge of extinction as it has a rich sociocultural heritage of people who have been involved in this craft since centuries. The circumstances are becoming more challenging for folk toy-makers and they have to supplement their incomes by involving in other trades. They are being compelled by the economic struggle to leave this ancestral heritage behind in the form of rich tradition and to work in factories. Folk toys have such a rich cultural and historical value that the toys can be traced back to Indus Valley Civilization.

Primarily, I documented 4 folk toys (Drum cart: Rehri, Clay horse: Ghughu Ghoray, Rattle: Damru, Wind fan: Pambeeri) and their making communities around the city. It is essential to pay attention as not only are these folk toys on the verge of disappearance but a rich inheritance of a community’s creativity and certain ways of their life and craftsmanship are seriously under threat. If not recognized and supported properly, might become extinct like many other crafts, and that would be a shame.

دن چار چوگان میں کھیل ، کھڑی ویکھاں

کون جِتے بازی کون ہارے

گھوڑا کون کا چاک چالاک چالے

ویکھاں ہاتھ ، ہمت کر ، کون ڈارے

اس جِیو پر بازیاں آن پڑیں

ویکھاں گو ئے میدان میں کون ہارے

ہائے ہائے جہان پکارتا ہے

سمجھ کھیل بازی شاہ حسین پیارے

(شاہ حسین)

Ameer Khan

Ameer Khan has been making these toys for the last 35 years upon his move to Lahore from a village, Banjar, which comes under Tehsil Talagang offshoots of Pothohar.

“When I was a child, I used to go to school, then we shifted to Lahore. I left school in Grade 1. When we moved to Lahore, we settled on Jail Road, now called Tollinton Market. I had 7 children in total, but four of them died in infancy: three survived, one girl and two boys.”

“My parents were basically farmers back in the village. When we migrated to Lahore, we learned this craft of toymaking. The primary reason for migrating from our village was ‘rozi’, (wage) there is no employment in the village. We learned this craft in our childhood; after migrating to Lahore, we had to do something, so my elder brother, Sakhi Muhammad, learned this craft from some people of Multan and taught the whole family. We have been doing it for many years, but our children are not interested in making these toys. My elder son makes them sometimes, but the younger one doesn’t like to sell.”

“My wife (Khatoon Bibi) used to make these toys, but she has become handicapped since the last four years. While sitting on the cot, she still makes some toys. It requires a lot of hard work and time; first of all, we have to cut bamboos into smaller parts, we convert used motorcycle tubes into rubber bands by cutting, preparing Dugga, muddy cups for Rehri, and for Dugdugi we have to mold cardboard skillfully. He concluded, “It does not return (monetarily) us the labour we invest in making these toys. He paused and replied, “Our hunger taught us to make these toys; there was a time when we did not have bicycles. We used to carry these toys on our shoulders to sell on the streets. We used to display them on the large bamboos. We learned about bicycles later; started hanging them on bamboos while lifting them on our shoulders right there at LOS, Tollinton Market; at that time, motorcycles were very rare. Now you see everybody is riding on a motorcycle, and it has replaced the bicycle.”

He started talking enthusiastically about the process of making Rehri. “First step is shaping the Dugga, a small piece of bamboo would be inserted in it, it will be left for drying under the sun. After it is dried it will be covered with thick paper and coloured. Secondly, two bamboo sticks will be picked and tied together by a rubber band, making the shape of V. Thirdly, the Dugga would be fixed in the middle of these V-shaped bamboos and tied from both sides with rubber bands. A pully would be fixed to the ends of the bamboos; a bamboo lever would be fixed between the pully and Dholaki‘s two tires. Finally, a string would be tied, making it ready to sell.” A sense of accomplishment was vivid on Ameer Khan’s face when he showed me the process. We can make 50 toys in a day if the raw material is ready. It requires a special kind of mud, Chikni Mitti, the one that is used for kiln ovens; if you dig soil from here and will try to make one, it will fall. This mud and raw material costs money. We go to Lohari Bazar to purchase cardboard, paper, and colors. The mud and bamboo are purchased from Ferozpur road. Used motorcycle tubes from motorcycle repairing shops and rubber soles are purchased from Kbaari.”

“I leave at 7/8 am in the morning from Babu Sabu and go to Model Town, Green Town, Muslim Town Mian Plaza, Karim Market, Johar Town, Ichara Bazar, Mozang, Gulberg and sometimes Shoe Market, we are not allowed to enter DHA. The guards don’t let us enter because, we are poor people, and the bicycles we carry are also second-rated; sometimes its chain derails, and sometimes I start dripping due to sweat”, He said smiling. “It takes an hour and a half to reach any market by bicycle ride.”

“We also used to make Juhnjhunay and Pakhay in the beginning when I used to sell these toys in Kachi Abadi, but now I go to these markets, so these three items are saleable.

After me, I don’t know if my children will carry on this craft or not. We cannot compel them. As long as I am alive, I will keep making them because of wages, and we are thankful to the Malik, who feeds us. I cannot claim that my grandsons will carry this (craft) forward; I am not sure. Danish Ali (Ameer’s grandson) sits with me while I make these toys. They observe us while we make them. Munir (Ameer’s youngest son) does what his heart says, sometimes, he helps me make toys, and sometimes he does not; he learnt the craft and then makes the toys but does not like to sell like me.

When there is off-season, especially in winters, I pull a donkey cart, and sometimes, if someone asks for daily labor, I go with them. We don’t have the option not to work because we have to earn anyway. He told me, smiling, that we are not literate and cannot work in offices. Munir, sells fish on the streets of Mozang, Ichra, Yateem Khana or Niagra, or Dubanpura. I go to the outskirts of Ravi on a cycle once a week to catch fish. Usually, I catch some. Otherwise, too, it is okay, Malik is the provider of Rozi. He provides sometimes smaller and occasionally larger, but he provides nonetheless”, he told me while pointing towards a pond on the drain bank. The fishpond is covered with a white net.

“We just demand that these toys have a single set cost, and whoever wants to buy one item should ask for one and pay us. We don’t need to bargain – a price should be set, no matter whether the buyer comes on a car, motorcycle, or anybody. The buyer should appreciate our hard work and craft. This is all we desire!”

I asked if you find something better than this work. Would you prefer to do that? He thought for a moment and replied, “I will give it a second thought, but I will not discontinue the craft of toy making because this is one thing that is close to my heart,” he finished smiling.

When I was a child, I used to play Gulli Danda, and Kenchy. He held his finger with the other hand to demonstrate, or we used to play with walnuts; I remember we used to make a toy called Khandoori, a ball made of leftover clothes; Ameer Khan told me the process of making Khandoori. We used to collect old useless clothes, soak them in water and tie it firmly. His hands were moving like he was making one when it became the size of a small ball, then we used to stitch it with needle and thread and later played with it just like cricket, but we had clubs instead of bats. We used to play all day before shifting to Lahore.

He added, smiling, “We used to graze flock of goats in the jungle all day and came back home in the evening.” We used to help our parents with the cultivation and harvest of wheat crops. I remember we used cattle as plough, now there are threshers and its done in minutes, in our time people used to stay in fields for months while cutting season of wheat, that was really hard work, today the Thresher (‘Penchod’) cuts 300/400 tons in a day, the cattle were plowed all the day starting from dawn to dusk, collect in an open courtyard, there used to be Taryangly used for dispersing the wheat. All the families used to be involved in this harvesting process, which separated the wheat straw from the wheat grains. Now every house has a grinding machine. At that time, Chaki, a manual grinder, was used, and my mother ground flour with Chaki and made us eat it; that bread had a sweet taste. Now, there is a drastic distinction between wheat flour and packaged flour, you keep on chewing with teeth, and it does not crush easily and doesn’t have taste even. It’s an old story I am telling you.”

Only men used to work in the fields. Women brought lunch and tea two times, and in the evening, one man used to sleep with crops, and the other one came home, and duties were shared on a rotational basis – turn by turn. The wheat was cut on a contract of 15/30 days, and when the cutting is done, the wheat grains were divided into two.”

Apart from it, we take care of cattle like the owner gives half money, and when the cattle are ready for sacrifice, they pay us half of the amount in return and keep half as “care money.”

He told me the story of children buying these toys. He was standing in Model Town, and a man with 6 children passed by. The children demanded to buy Pakhas. Later a child held Dudugi and beat it when it produced a sound, so he was more inclined to buy Dugdugi, and all six of them bought Dugdugis; he said smiling that on the road, all 6 children beat the Dudugis. It depends on the mood of children, and some parents ask children to buy as a memory piece of their forefathers and children deny, in some cases, if parents don’t let them buy the children cry….”

He told the story of an FC (Army Officer) with a long beard, “He gives me so much respect that he invites me for breakfast at a nearby shop and makes me sit at the same table as his family sits for breakfast. When he does, he plays with Dugdugi in front of his wife and pulls Rerhi and laughs and tells with great joy that this is the toy of our times and asserts that the children buy the toys – whether children want to purchase or not, he buys and keeps them in his car. He not only pays for breakfast but also buys the toys and appreciates me by giving me some extra money, he stressed. “An FC wearing three stars on his shoulder,” Ameer Khan repeated, “It’s not as if he makes me sit on the ground with the breakfast. Rather he asks me to sit alongside him.”

Ameer Khan goes to Model Town B Block Market every Sunday. I have asked permission from him if I could accompany him on his next visit, and he generously permitted. It was a cloudy, cold morning in December of 2021. Before leaving my place, I wanted to confirm if he was coming, as it was a bit drizzly outside. I called on his mobile phone, and his wife, Khatoon Bibi picked up the phone and said, “Your Mamu did not take the mobile phone because he was afraid the phone would soak due to rain,” she took a pause and spoke sadly, “We are worried that the toys might have gotten wet in the rain; it’s raining since morning, but he is still gone.” I could sense the fragility of the moment and took an uber bike and reached Model Town B Block Market. I started searching for him near the landmark he told me. I could not find him but saw his cycle standing under a shop’s shade. I went to the cycle and saw Ameer Khan approaching me, with a smile, as always, and holding the tea in a paper cup. I warmly greeted him, and he began, “I did not bring a phone because it was raining,” and he offered me tea, and asked me if I had my breakfast yet or whether he could bring me some. I was so overwhelmed by the love he showed every time to me.

After finishing his tea, he held the Dugduggi and started beating it to attract the audience to the heavy noise. The impatient fancy motors accompanied the sound of Nan baking in a nearby traditional Lahori cuisine shop. He told me that these days, sale is not so much. He stayed in this market till 2 pm and left by taking a circle to C-Block market to sometimes successfully sell some toys there. Later, he rode his bicycle back home. He said, “I don’t have a watch, but probably it takes me one hour from Babu Sabu to Model Town on my bicycle. You know how cold it is these days, but when I reach here, I am dripping with sweat, especially my head, and I get it dried with a handkerchief before covering it with a warm cap so that it does not catch the cold air.”

He requested me to take photos with his wife to save as Yadgeeri, “who knows how much time she has,” (his wife is sick) and asked me to share whatever the expenses are spent on printing. I tried to refuse payment, saying it was alright, but he insisted. I could sense the dignity in his insistence.

He also requested to do him a favor regarding the guards of Model Town as they admonish him while he comes to sell his toys. I had just come to sell toys, but they pressurized me and asked me to leave model town. He shared that a while ago, a guard came on Honda 125 and scolded me to leave, but this Puri maker came forward and said, “You all are after this poor toy seller, while no one admonishes the beggars who disturb visitors on cars. He is standing in front of my shop.” Ameer Khan added, “The guard silently had to take leave.”

Ammer Khan started telling me that he had been coming to this market for 15 years; there were rarely any guards around at that time, and every shopkeeper here knew me very well. These guards were deployed a few years back. One day a guard came to me and threatened me to leave, and there was a kind shopkeeper who gave me a chair to sit on in resistance to the guard. The shopkeeper and guard had an argument. The shopkeeper supported me and dismissed the guard by telling him to go and report to the security office – meanwhile, he (Ameer Khan) is standing in front of my shop; do whatever you can. He was beating the Dugdugi continually and interacting with local shopkeepers. He told me that the Nashta shopkeeper gives him Nashta every Sunday for 60 rupees. He was trying to register that all the shopkeepers protect him and provide him with respect. He told me that the area of Defence is the wealthiest area of Lahore. There are chances that people buy my toys in a large number, but the security does not let me enter.

He moved his cycle limping, and I asked the reason for his posture and pace. He replied that he was wearing the shoes of Munir (his son) and shoes are not of his size, so that is why he is having trouble because the big toes are being shackled.

He told me that before I arrived that morning, there came nine children and all of them bought Dugduggis, and they started playing in a choir formation, and it looked like a juggler’s show. He was smiling while telling me of this incident.

He started pulling his bicycle and moved from B-Block, and I accompanied him towards C Block on foot; he was beating the Dugdugi while walking with the bicycle. At the C Block market corner, a car stopped by and bought a few toys. The kids in the car started playing the Dugdugi enthusiastically while the mother slid the windowpane up. Ameer Khan rode on the cycle and started his journey back to his house.

Khatoon Bibi

I was in search of folk toymakers and visiting outskirts of Lahore as most of the people told me that they had seen gypsies only selling these on the streets, while carrying a wooden handmade basket or on cycles. Through an NGO that works with these gypsies, I found a tent settlement in between a city sewage drain and Babu Sabu interchange Motorway.

On a Smoggy morning of December 2021, I was just passing by this lane that my eyes found these colorful toys surging on a cycle parked inside the tent of 30X 20 feet. The whole settlement of 25/30 tent-houses make these toys for living. A young girl in her early twenties was engaged in domestic chores. A lady in her fifties, lying on an ironed cot looked at me suspiciously. After greeting her I asked permission, if I might come inside the tent and see the toys hanging with a bamboo rod along the cycle. She permitted hesitantly and I went inside paid attention to the toys. she inquired if I was interested to buy these toys and I tried to tell her I am studying about these toys. She gave a surprising gesture by replying, “Can toys be used for study purpose as well?”

A boy (Khatoon Bibi’s youngest son, Munir) of 25 appeared carrying a donkey cart loaded by wooden fruit crates, unharnessed the donkey knotted it with a peg put fodder barrel in front of it by refilling it. He greeted and started unloading the crates by separating newspaper. The crates had some leftover oranges, a boy (Khatoon Bibi’s grandson, Danish Ali) of 3 years having a long-spared tussock and rest of the head is trimmed, wearing brown qameez came quickly and picked up those oranges and started eating by peeling with his teeth. Munir; found some more oranges a little bruised and threw them into donkey’s fodder barrel.

Khatoon Bibi, wife of Ameer Khan, started sharing that she had been on the bed since last four years. She is unable to stand still on her feet. She seeks help from her daughter-in-law or Munir for visiting washroom. Adding on, she has been brought to hospital when pain exceeds but medicines are of no avail. Her daughter-in-law brought the wooden crates inside the tent and started turning on fire by putting those crates as a fuel in a grate made by mud bricks. The daughter-in-law named Bholi brought water in a steel glass from a government supply pipe tap fixed right at the bank of ‘Nala’-drain and gave medicine to the lady. She carried on by saying, “Who knows someone from ‘shreeka’-in-laws- has put ‘Waar’-magic- on her that is why the medicine is not working. “Mola! Will listen to me and lessen my pain INSHALLAH.” She asked me, if I know anyone who does Dum Drood as the whole family is worried about the me as I am bed ridden since last four years.

The boy of three years named Danish has some speech issue as her grandmother was telling that he does not speak though he has come to the age of speaking. They think he also under some Waar.

Bholi started preparing for lunch by placing Saag on the grate the smoke of wood was also warming the tent in the freezing morning of December. The old lady shared happily that her daughter sent this Saag from her village. When I asked that, who makes and sells these toys, she replied my husband makes and goes on Pheri.

After half an hour a man in his fifties came and started telling a bit angrily, that the mobile repairer was not on the shop. He added, the person to whom they handed over the mobile was kept on delaying, and they had been paying visits since last six months for fixing it. It took time and money as the he had to pay rikshaw fair for reaching the technician shop. The old lady responded, they faced difficulty connecting to her daughter back in their village; Talagang. The little buttoned Chinese manufactured is the only source of connection to speak her daughter (Shazia) and elder son named Tanvir.

Later the toymaker inquired about my presence and the lady told puling her eyebrows up, that I am studying these toys. He turned towards me showing a mixed reaction of enthusiasm and surprise, “Why would someone consider these valueless toys for studies?” He added sadly, he is not making and selling any new toys due to severe cold. He asked his daughter-in-law if they offered me a Chaye ans asked me if I don’t take tea, he can bring a bottle as well. He shared, “It’s a Hawai Rozi; inconsistent livelihood, sometimes it pays you in form of 400/500 rupees and sometimes you come back penniless,” “My own younger son thinks, these toymaking activity is not of any worth and he prefers going to cattle auction with the surety he would not come back home empty handedly in the evening” Ameer Khan gave a silent pause after saying this. He looked in space and suddenly brought something back, “There was a time in 80s when people used to feel proud having this skill of toymaking but it’s fading out with the passage of time.” He seemed sad that his offspring is not carrying forward the craft of toymaking as he feels this is the last Perhi of these toymakers and none is willing to take this rich craft forward.

A boy(Khatoon Bibi’s grandson) of ten years came in with some brightly colored card sheets and asked his grandmother to cut these he wanted to make some Pambeeris; Wind fans out of them. She held scissors in her hands while I could see swollen arms of her. Ameer Khan started pressing the sheets through artistic mastery and she started cutting it skillfully. She also showed and taught me how to cut these avidly to make Pakhas. Khatoon Bibi shared “There are two consumers left of these toys; the people who are film industry and teachers they order beforehand that they need a certain amount, and we prepare before they come to pick-up their order.” Faces of both husband and wife had strange kind of satisfaction and fulfillment when they were engaged pressing and cutting those cards.

Once I caught cold and I could not visit them for a month, but I gave them my mobile number so, Khatoon Bibi called me and asked, “Why didn’t I come since a month?” So, I told her that I caught cold so she told a ‘totka’-remedy- to me that would cure my congested chest. She said, whenever I will visit them, she would spare some Desi eggs of her domestic hen. When I visited them after recovering Khatoon Bibi instructed Bholi to make tea and boil an egg for me. When I was coming back home, she gave me two eggs and said, “mix them in hot milk and your chest would be perfect in the morning.” For the whole winter season, whenever I visited her, she gave me a boiled egg and cup of tea and whenever I insisted not to take she responded, “Aren’t you a son of mine?” When I recovered fully so once she called me and said, “Your elder brother, Tanvir sent peanuts (Tanvir works in peanut fields back in their village) for us and I have spared your portion and when I said, “That is so kind of you, but you can eat them” and she responded with determination, “That is your portion I am saying my youngest son, Waqas’s portion.” When I visited next time after this phone call, she silently kept a shopping bag of peanuts on my bag, and I could not resist returning that.

Sakhi Muhammad

It was a cold, cloudy evening in the beginning of January 2021. I was sitting on a cot outside of Ameer Khan’s tent-house when I saw a person of six feet coming towards me hobbling. He was, in his sixties, wearing a chocolate brown shalwar kameez, covering the head with a brown pakol, keeping a thick and lengthy mustache, eyes were brimming with Surma and he was wearing a brown Gargaabi in feet. For a moment, I thought some retired security guard was coming; later, Khatoon Bibi told me he was the younger brother of Meeru (Ameer Khan is called Meeru by love).

He was curious to know about my arrival and keen to know the reason I was there but also suspicious that maybe I was a news journalist. But I told him I am working on the toys they make.

There was shine in his Surma-laden eyes when I mentioned the toys. He told me “I had been interviewed many times, and people came to me and asked for interviews, but I knew what the purpose behind it was. I refused many, but I will give you an interview someday,” he finished on this note.

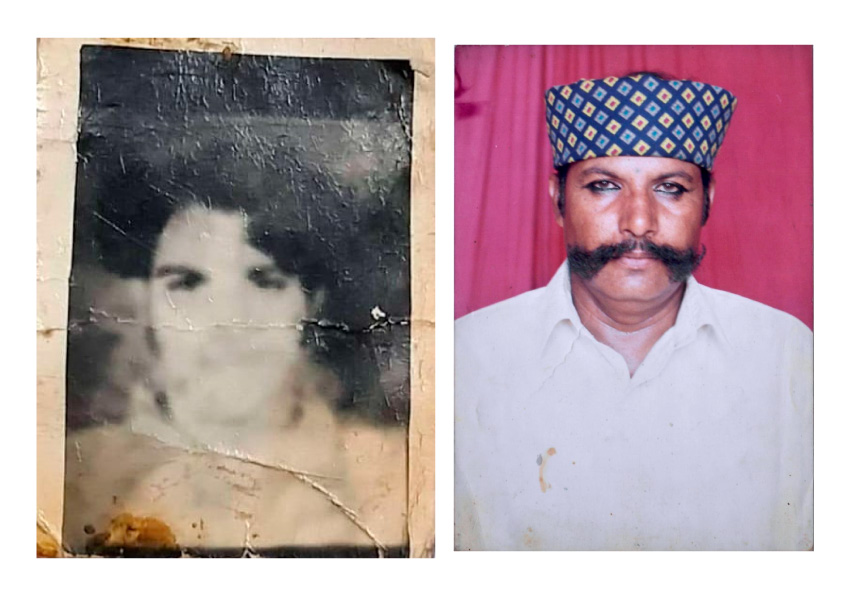

He continued, “My father was in jail for 14 years in a suspected murder case. I was 6 years old at that time.” After a pause, he started sharing that he (Sakhi Muhammad) had been involved in many court cases back then in his village. “I was 14 years old when I eloped with a girl; it was my first marriage.” He opened his wallet and showed me a blurred black and white passport size picture. “I have married four times, and every single time I eloped,” he carried on proudly.

“I used to be dandy in my prime age, even once Lollywood people came and offered me to work with them in Punjabi movies, I was also interested and willing to go in showbiz, but my mother and my sister started crying if the people would misuse me, so I gave up.”

———–

“I spent most of my life eloping with girls, and in courts, I had been notorious in my hometown but time does not stay same, the prime age comes and goes, there is a proverb: the of a scoundrel and a prostitute is always bad; I escaped by 25/26 court cases, eloped with four women, and also helped 10/15 people arranging elopements that’s another story, now the end seems weaker, and I know whatever I have done has consequences, but if God is blessed, He will forgive me….”

“I went on Pheri after many days because the streets are mostly empty in the cold weather and toys start absorbing moisture, so I came back earlier today.” Sakhi Muhammad said. He told a story of someone whom he met on the street, “I think he was representative (of some official) he asked me for an interview, I refused him as I thought he was fraudulent and said he would arrange some money for me even asked for my mobile number and further details, but I refused. He kept insisting to inquire about my place of residence, “I told him I live in Talagang, can you come there? If you want to help, you can find me on these streets. I understand there are good people, but there are devils; we are poor people.”

One day I asked him if I could accompany him while he was on Pheri. He shared that his route starts from his house in Babu Sabu on a cycle at around 7 am. My 1st stop is at Ichra canal, Ichra Bazar, Shama stop and Mozang Bazar, Railway station sometimes Anarkali Phatak from there I come back on cycle. He added nobody knows where I go on Pheri, even my elder brother. He said there is always a better sale on the roads than streets as sometimes rich people come and buy these toys, and they pay 50 rupees per item, and on the road, I sell 15 to 20 items, and they give enough money for daily expenses. The item is sold between 10 to 30 rupees on the streets maximum. So, he said you cannot come along and take pictures while I am in Bazar because there would be females shopping in the bazaars, and they would mind it, and they would not allow me to sell these toys in these Bazar if you came along to film.

“Waqas, I met a man a year ago, I observed, he seems fraudulent, he asked if I have a change of 5000 rupees, I will give you 500 rupees (as a gift). I told him, you seem sane and a Sufi,

I even don’t have toys costing 5 thousand rupees on my cycle, and you are asking for change.” Sakhi Muhammad continued, “I sell them at the rate between 20-50, and there is a shopping mall right in front of you; instead of gifting me 500 hundred, why don’t you go and get a change of 5000 rupees? I have been coming to these streets for the last 30/40 years. You can’t play me.” “I had 500-600 in my pocket at that time, but I told him I had 50 rupees; I knew if I told him the truth, he would trick me and run away on his bike” Sakhi Muhammad concluded, “In big cities, people try to deceive you; they cannot make their ends meet. God will catch them in the other world while in the grave.”

Sakhi Muhammad told me another story of his father, “There was a time when my father used to sell these toys. One day a young man came and asked him to give him all the change he possessed. The young man would return his father 500 rupees, the old man gave him whatever he had and kept on waiting for the young man and asked some people on the streets if they had seen such a young man, but nobody recognized at the end, my old man came back home empty-handed.”

He continued with the stories of how his father had been wronged by several others. Once his father was searching for daily wages somebody asked him to fetch some soil, and the old man started doing that it was a hot day, and the old man removed his shirt and Salooka – vest with pockets – when he finished fetching soil the old man found that his Salookawas stolen by somebody as it had some money in it. “We’ve had to learn how to live in a city life as we have to stay vigilant in the city; it’s a place of fraudulence.”

Sakhi Muhammad gave me some pictures of his parents to get them framed in a larger size, and he gave me his old passport size photo from when he was 14 years old as well; he also wanted to get that one larger, and one framed because he thinks it will stay with his children as ‘Yadgeeri‘ – memories – so I had them enlarged and framed, bringing them to him at the beginning of February.

When I went to deliver his pictures, he invited me to his tent-house for the first time. It was a 20 x 16 tent house with a small kitchen made of mud. While entering the tent-house, two wooden charpais were lying left and right, leaving the space in the center that ends with large trunks covered by colorful frills. Some posters of Sufis (Shahbaz Qalandar, Data Sahib) were hanging along the roof in the center of the tent-house.

He asked me to sit on a charpai and gave me a pillow with beautifully hand embroidered red flowers. I had won his trust, so he let me come into his house. He lives in this tent with his elder son, who sells coloured fish on the streets.

He went limping towards one of the trunks and brought a black bag. He had some pictures from the past. Some from his youth and some were of his married children. I was shocked to witness his daughter’s stunning jewelry and dress from her marriage. He showed me pictures of all his four wives. He wanted to get one of his pictures photoshopped with one of his wives, who died some years ago. He told me he has 5 children from his last wife, who lives back in Talagang with his children, and a daughter from another wife. He shared that two of his wives died, whereas one he divorced. I could see sadness coming over his eyes while sharing pictures of his deceased former wives. “I have pictures of all my family members, and I keep them as Yadgeeri; my children will have them after my death.” He told me all this while pointing out his relationship with the person in the picture on every picture. When I asked if I could take these pictures and would return after scanning, he thought for a moment. He refused by saying here are photos of my family (female) members, and I am afraid it might be found on the internet, and everyone has a touch mobile so….” Later he gave me some of his portraits and said it was okay if his pictures were to be circulated on the internet. He counted the photographs and asked me to keep them with care because these are of much importance to him, and he asked me to return in 3-4 days. He concluded, “I never showed these pictures to anyone but my children and you, and I trust you as my son.”

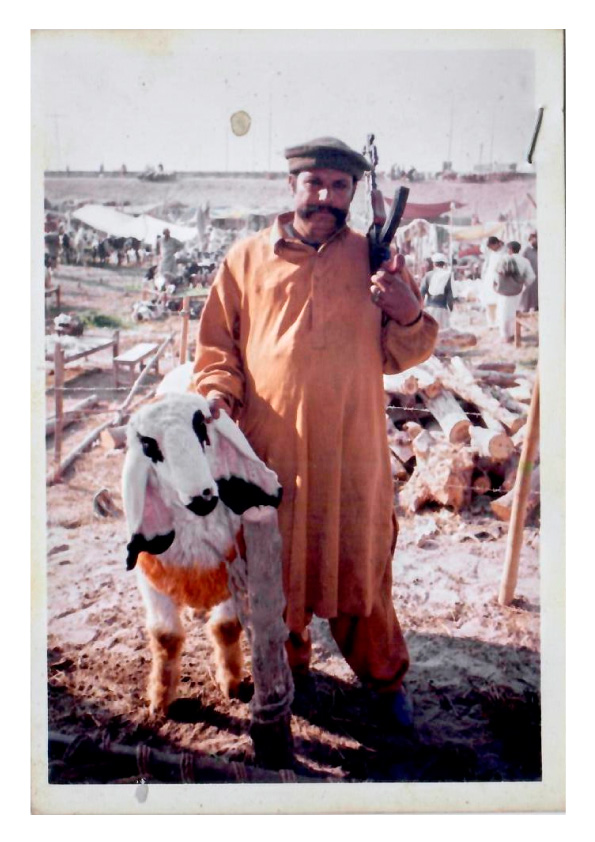

While putting the pictures in order, he showed me pictures of buffalos and goats. He said he sometimes worked as a caretaker for buffalos and goats. The people used to buy us these cattle, and we used to care for them till Eid-ul-Azha, and they paid us for the fodder and caretaking.

When I was a toddler, my father had Pashtoon friends in Peshawar. When I was 6/7 months old, they came to see me, and their wives made this mole on my forehead with a needle to save me from ‘Nazar-e-bad’Bad omen. My mother told me I cried a lot. They opened it with a needle, added Surma, and later pinned it up. When I was 8/9 years old, they asked my mother to see how beautiful this Dimi looked to him. Its tradition of India you know, here you can find this tradition in Peshawar. After the death of my father, they did not visit us.

Munir Ahmad

Munir Ahmad is 25 years old and he is youngest son of Ameer Khan. He does multiple jobs mostly dependent on the season and need. He goes to auction of buffaloes and helps people fix a deal for animals and this work goes till Eid-ul-Azha. When there is an off season of animal auction, he catches colourful fish from a distant side of river Ravi and sells on the streets. If there are no fish in the river, he goes on daily wages labour. In the winter season he goes back to his village, Talagang and sows peanuts and stays there in the village until they get peanut crop. He helps Ameer Khan for preparing the toys, but he doesn’t like to sell them as he thinks they don’t pay well. He turned into a wedlock with Bholi in the start of 2021.

He is fond of animals and birds. He has 80 pigeons of different species. He has hens, cocks and a quail.

Margaret Joseph

Margaret Joseph, a physiotherapist has 40 years of experience in physiotherapy. She spent her childhood in a village adjacent to Sheikhupura. She lives in Youhanabad with her sons and daughters. When I went to interview Ms. Margaret, one of her grandsons named Erie, aged 10, was playing a cars video game on an LED linked with a wireless handle. Another grandson was playing with a rubber-based hand toy. Zona, aged 8, the grand daughter of Ms. Margaret was insisting to give Zona the mobile phone as she wanted to play a video game. Later I found Zona playing on a tab.

Ms. Margaret started talking after seeing Ghughu Ghory, Damru and Rehri, “I remember our mothers could not afford these toys, so they encouraged us to learn to make these toys on our own, this (Damru) called Jhunjhana now, but we used to call it ‘Dib Dib’. Our father used to bring us these bamboo sticks and we played in mud most of our childhood. The mud that is used to make earthen pots is called ‘Paan Mitti’ it was transported from a bit far and we used to bring it later grind it, add water at the night before we kneaded it for toys. We made bulls, I think this Ghora (that I had brought) is not so beautiful as we made in our childhood. I remember these toys were also part of our education in our schools. We used to be graded on these toys. We made mud houses, we made buffalos, ‘Chaati’ ‘Madhaani’ everything was made of mud. These toys were also source of education for real life preparation.”

She related a vivid memory, “When we used to come back from school, I remember we had a big tree on Neem in our house and under the shade of that tree we made these toys with a niece of mine. There used to be ‘Ghugghu’-mud whistle- made of mud I remember when we used to blow it, it created a sound of whistle. Small ‘Chakis’-wheat grinders- of mud, our mother used to buy us as well as encouraged to make our own as well. My 3rd generation is going on now and my daughters and sons have played with these toys as I made sure to introduce them to these toys in their childhood. We never wasted our rough copy and used to make Pambeeri-wind fan- of the rough pages and now this generation doesn’t like these toys and they also don’t like to make because of ‘Jadeediat’-modernization. I have a brother who used to make ‘Gadda’-a bull cart- of mud. My mother told us these are not baked, and she taught us how to bake them by making a ditch in the ground, we put these toys in the ditch and burnt a cow dung-based fuel to bake these toys. Specially the tires of ‘Gadda’ so they don’t break. The same brother of mine later started making a tractor of mud with the passage of time toys also started transforming. But now my 3rd generation asks for mobile, TV, LCD and computer, just these gadgets. These toys were real world to us like a mud-based buffalo was treated like a real buffalo as a pet.”

“In the evenings we used to go out at the bank of a pond just like children go to parks now, we used to go into the pond and brought out mud from there it was the best mud to make toys. We made houses having all sorts of house-based items the house used to have a boundary wall. This all was done mostly by girls because they are fond of making homes. We had boys in our company as well, our brothers as well as boys of neighborhood, now we don’t allow our girls to go out and play. I remember, we used to play ‘Lukan Meeti’-hide and seek- in the evenings. While passing from every house in the neighborhood we used to knock at doors, boys and girls joined us in the play and became a ‘Caravan’-group-. Boys accompanied us in all sorts of plays, sometimes we were stopped to play but we still played with boys because we did not have anything negative on our minds. We used to give ‘Chogha’-to share edibles- each other without even thinking that we have boys in our company as well.”

“Our mother taught us how to make a stuffed doll by utilizing old useless clothes we used to cut our own hair and fixed on the head of doll with glue. My father brought me a doll that I kept close all my childhood and never gave to anyone else.” Ms. Margaret shared a folk song related to dolls, she took a pause, and her eyes were full of tears.

بابل میریاں گُڈیاں تیرے گھر ریہہ گیئاں۔۔۔

My dear father I have forgotten my dolls at your house…

There are many sentiments attached to this tradition of marrying daughters and dolls used as symbols of this tradition.

Jannat Ali

Jannat Ali is a Lahore based Artivist. She has been advocating for transgender rights in Pakistan and is at the forefront of this struggle. She is a classical dancer, actor and a host. She started the 1st transgender hosted show in Pakistan, titled, “Journey with Jannat.”

She shared about her childhood, “In the beginning, like at the age of 6 I had the space, being a trans person I wasn’t stopped from playing with any gender specific toys, based on societal norms but the later experience as I was growing up started taking sharp turns. As a child I was more inclined towards dolls. I don’t categorize toys based on stereotypical gender segregation. I used to play with dolls and tried to stylize them by putting different kinds of dresses on them, styling their hair. I used watercolour for applying make-up on the dolls as well as on my face but when my mother used to come to me, I instantly washed my face.

The most vivid memory of my childhood with the toys is one in that I used to invite all my cousins for some kind of children’s party. We all used to bring one dish and eat together. I was so fond of collecting all my cousins for a gathering or celebration, I remember I used to choose such toys which have some margin of leading an event. I remember another event related to toys I used to own a stuffed teddy bear that I have given to my niece now, I used to talk to it, share my feelings when nobody understood me, I kept it with me telling stories at bedtime. It was so close to me.”

“I think toys are planned according to the needs, fashion and culture of a particular area and it changes with the passage of time, for example, in olden times we used to have our own folk doll but with the influence of west some notions were endorsed through toys. Barbie is an example of that. As they made Barbie a demanding toy and some other items linked to that for instance Barbie’s Doll House. You would never find a toy set that has something to do with our village culture just like a Barbie house, you would never find a Village house. Then started coming automatic toys, remote control cars, gadgets and then came mobile phone and the talking toys like having Indian songs being played back mostly, I don’t think there was any research behind this. I never found any toy that played Pakistani songs. I don’t know who used to decide all this, they were manufactured in China, songs were of India and used as playthings in Pakistan. I think it has something to do with cultural and political stances behind this.”

While talking about local Guddi-doll- she told, “Our local folk doll represented local facial features like South Asians, large eyes, its nose used to be pierced and most importantly the cultural dresses it dressed in. It used to carry Gharra-pitcher- in hand and sometimes a Pankha-hand fand- so you can tell it was our own doll. I mostly saw this local doll on Melas-cultural carnvals- only. I also witnessed class system in these toys like upper middle children will have electric battery cars or Barbies. I never saw the children coming from this middle or upper middle class playing with local toys. I think from here discrimination starts that children start having an understanding that with which toys they can play and with which they can’t.”

“I found a video of mine a few days back in which I was playing with flowers and stylizing a doll by transforming buntings into a hand purse and I told my parents that I was a trans-person since beginning and you always blamed that I had an influence because of my friends. I find myself playing with doll and my mother never let me buy a doll, so I used to borrow from my cousins and played. I used to stitch clothes for and after a particular age. I remember, arranging a wedding of my doll, prepared its dowry and when there was time of Rukhsati-bride’s departure- I started weeping and felt like a mother feels at the time of her daughter’s wedding. I remember my brother used to show wrath towards my doll and sometimes beat it and I stopped him from doing that by saying it’s also a human.”

Ghoray Shah

Here in Lahore, there is shrine near Baghbanpura, the shrine is called Ghory Shah because of the person who is buried there. For the longest period of time many of the locals even did not know the real name of the person.

The legend of Ghoray Shah is told as, “Ghoray Shah was much inclined towards horses as a child and whenever anyone used to bring horses for him as gift he prayed, and their wishes were fulfilled. So, this had become a practice in the 16thcentury that people used to bring horses for getting their wishes fulfilled and this made his father angry, and he scolded Ghoray Shah and it is told he died at the age of five only.” This practice of presenting horses on his shrine was going on since the last four centuries until a few years back a religious extremist group took a hold and whitewashed wherever Ghoray Shah was written and replaced it with Makhdoom Bahaudin. The group has also built a fancy Madrasah right in front of the shrine and a Mullah also has been designated for Quran classes on a daily basis. There used to be a Mela every year that has also been converted to Mehfil-e-Naat. The locals seem angry about this replacement as they have been following this tradition of Ghoray as Nazar Niaz at the shrine.

If now you visit the shrine, you cannot find the Ghora craftspeople who had been removed from the neighborhood as the religious group brought this argument that these Ghoray are made of clay and statues are also made of clay and statues are Haraam in Islam. I came to know that these craftspeople have started making clay lamps as they have to earn anyway. The craftspeople who still make these clay horses, but they (Ghora toy makers) don’t want it to be exposed and they refused that they make now.

The traces of such clay toy making have also been found in the Indus Civilization archaeological remains. So, the story of clay toymaking has a rich history which is possibly five thousand years old.