Five Pounds in My Pocket

BY Shaista Chishti

MENTORS: Wendy Marijnissen

PAKISTAN PHOTO FESTIVAL FELLOWSHIP 2017 PROJECT

In April 2001, nine per cent of all 1.6 million British Muslims and 16 per cent of Britain’s entire Pakistani population of 658,000 were found to be in the city of Birmingham. In 2001, nearly one in ten of all British Muslims were found in Birmingham, arguably home to the world’s largest expatriate Azad Kashimiri community..

Migration to Britain

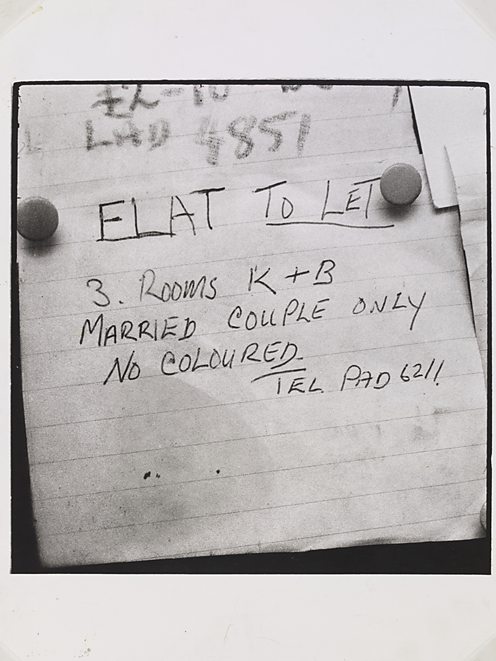

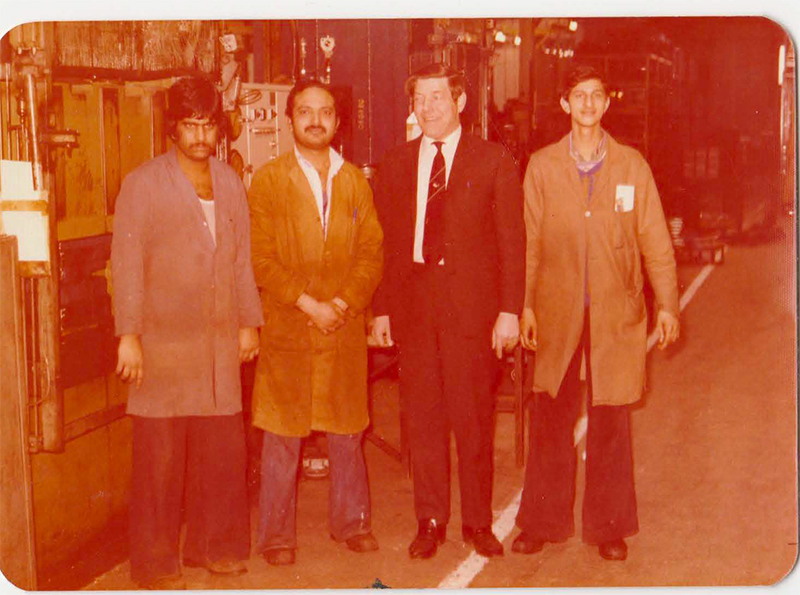

When the earliest settlers came ashore during the 1930s, industrial jobs were virtually impossible to obtain, so most followed the longstanding tradition of making a living as itinerant pedlars. During the Second World War the number of settlers grew rapidly. Britain’s heavy industries were short of labour, so that not only did many former pedlars switch to industrial jobs, but Pakistani seamen who had had their ships torpedoed beneath them soon found themselves drafted off to work in munitions factories in Yorkshire and the West Midlands. Once transport was available after the close of hostilities some went home with their accumulated savings, but most stayed on to take advantage of the opportunities that became available in the post-war industrial boom. The jobs open to migrants were of a restricted kind – essentially those which the indigenous population were unwilling to undertake, because they were hot, hard, heavy, or low paid. But to many they offered the prospect of prosperity.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s an increasing number of seamen left their ships to take industrial jobs on shore, and soon afterwards began actively to call kinsmen and fellow villagers over to join them; it was thus that a process of chain migration began. Until 1962, Commonwealth citizens had an unrestricted right of entry into Britain, and the steady inflow of settlers was essentially a response to the almost continual growth in demand for unskilled industrial labour. But in response to popular protests from the indigenous majority, a whole series of measures to control the influx of (non-European) immigrants have since been taken. The first of these, the 1962 Immigration Act.

Using estimates, it is possible to determine that the British Muslim population has grown from around 21,000 in 1951 to 1.6m in 2001. According to the 2001 Census, in the city of Birmingham, home to 1m people, Muslims account for 14.3 per cent of the population, with Pakistanis numbering just over 104,000 (74% of Muslims in Birmingham). This number is twice as large as the highest concentration of Muslims outside of London (ONS, 2005).

In April 2001, nine per cent of all 1.6 million British Muslims and 16 per cent of Britain’s entire Pakistani population of 658,000 were found to be in the city of Birmingham. In 2001, nearly one in ten of all British Muslims were found in Birmingham, arguably home to the world’s largest expatriate Azad Kashimiri community.

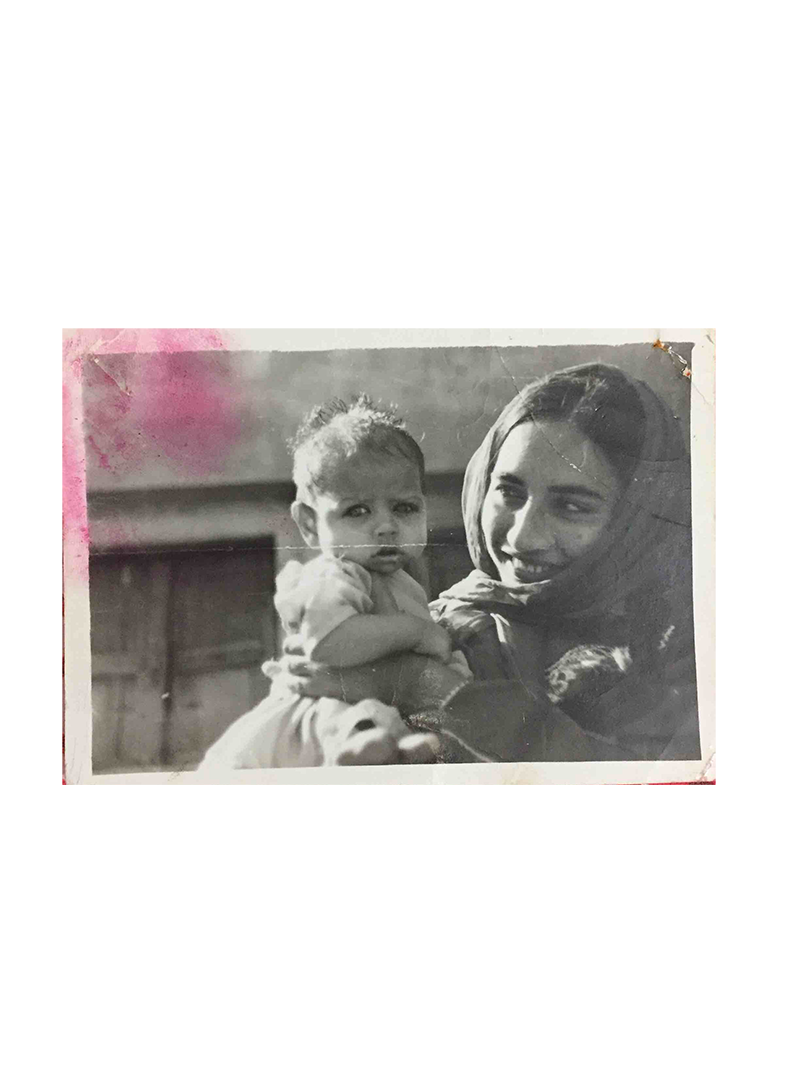

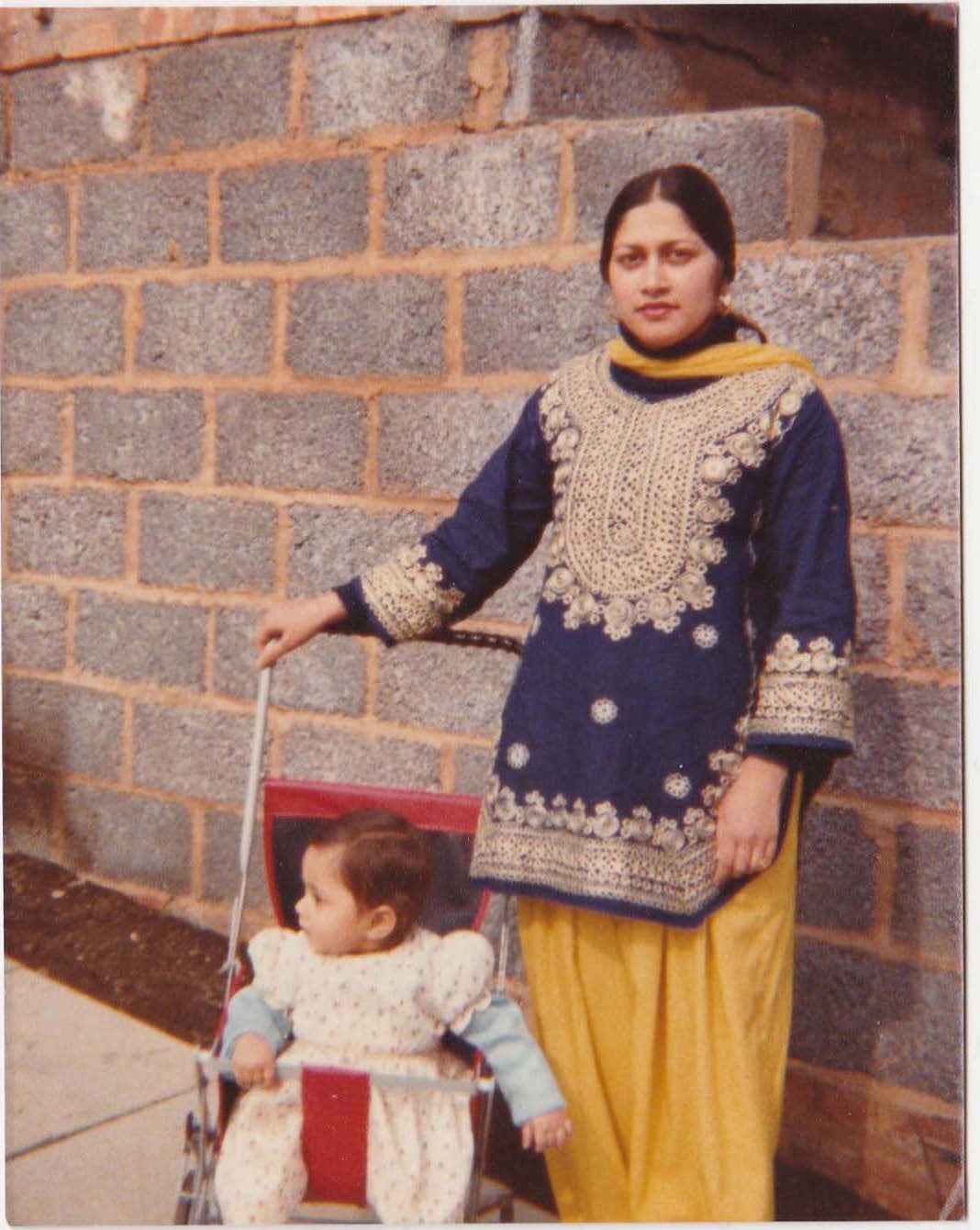

Pakistanis do not necessarily comprise a single homogeneous religio-ethnic group: ethnically, there are Punjabis, Kashmiris, Pathans, Sindhis and Blauchis who are all Pakistani. As a result of the building of the Mangla Dam in North West Pakistan, which uprooted many families, men of working age were sent to places such as Birmingham to join the existing male numbers. Many arrived in this way, followed by wives, children and fiancés, who came to join men in order to unify families and form communities. As such, as much as there is a great deal of homogeneity among Muslims in Britain there is also considerable heterogeneity, particularly in Birmingham with its large Pakistani, or more specifically, Azad Kashimiri communities.

A proliferation of Mosques is sign of a definitive commitment to the development of Islam in Britain and the teaching of younger Muslims the practices of the religion. Specialist goods and services outlets such as Halal butchers, Madrassas (Qura’nic schools), grocers, restaurants, takeaways, jewellers, bookshops and Urdu-Arabic audio/video retail outlets are familiar sights in the concentrated multi-ethnic enterprise economies that many live and work in. Post-war South Asian Muslims largely entered and settled in Britain as a workforce for the unwanted jobs indigenous people did not wish to carry out anymore. Today, Pakistani and Azad Kashmiri groups continue to live excluded lives, existing near or at the bottom of local area economic and social contexts, largely in post-industrial cities to the North, Midlands and the South, all of which at various stages of regeneration after the collapse of traditional industries. The fact that one-in eight of working Pakistani men is Britain a taxi driver is indicative of the marginal nature of communities. British Pakistanis, new and old, is the economic and social positions they possess.

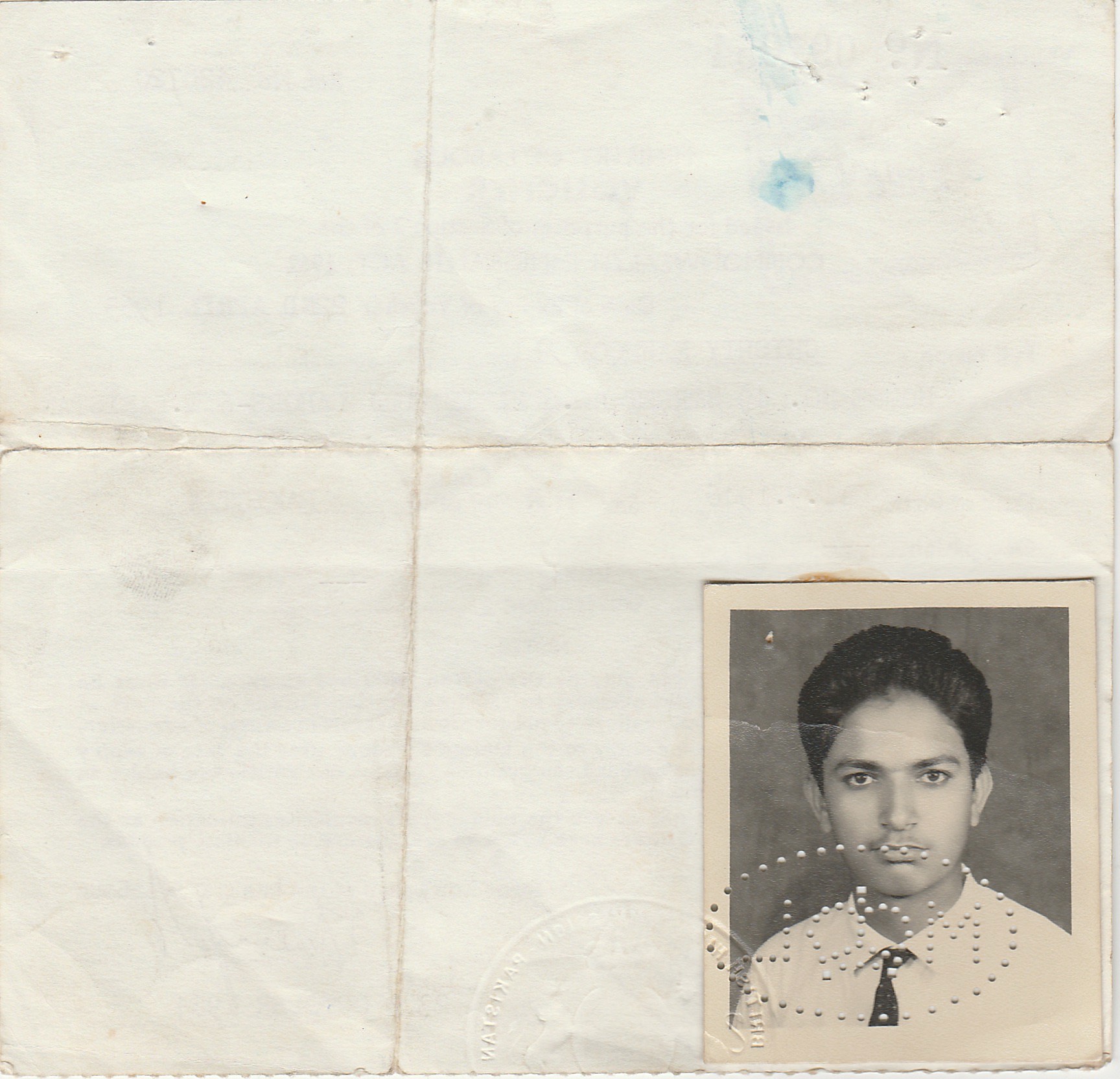

The Story of Mashriq

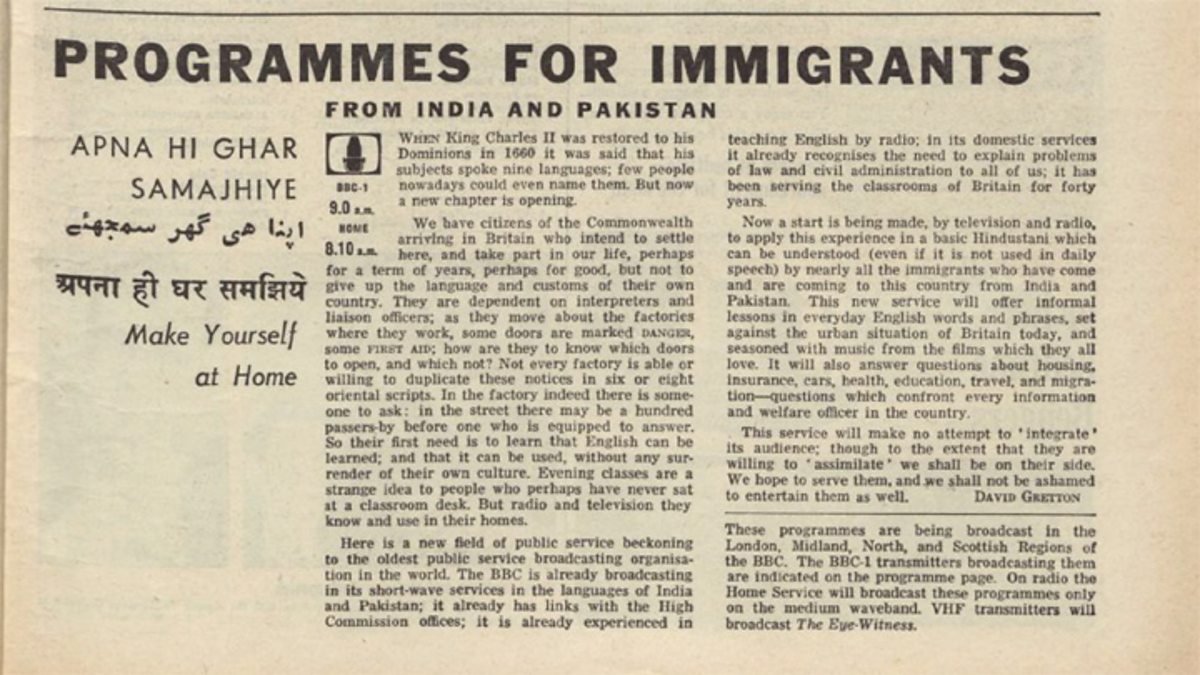

When Britain was busy rebuilding as quickly as possible the cities and factories that had been destroyed in the war. Britain was in urgent need of manpower. Its doors were open, and hardy, hardworking villagers from Mirpur and Panjab were arriving in droves. These were the days when the star of illiterate laborers was in the ascendant in Britain. One or two educated people were arriving too, but in comparison with the illiterate laborers their achievement was not at all impressive. Most of them considered it an insult to them and to their university degrees to be offered work in a factory, and the British were not prepared to attach the importance to their degrees that they thought they deserved. True, some of them came to terms with this situation; they forgot about their B.A.s and M.A.s and began to work side by side with their fellow countrymen, some of them as conductors, some of them as porters on the railway, some of them as postmen. The British took a real liking to those Pakistanis and Indians who couldn’t say anything beyond “yes,” “no,” “okay,” and “thank you,” and who, when any white manager or foreman spoke to them in English would gesture with both hands and with a very innocent smile would say “Me no Hindustan,” that is, “me no understand,” that is, “I don’t understand,” that is, “I don’t understand English.” The factory foremen and managers felt really fond of these simple, harmless, hardworking creatures who simply minded their own business.

The meanings of quite a few English words had changed. Here “dinner” didn’t mean the evening meal but the midday meal. If you met somebody after dark and greeted him at first meeting with “Goodnight,” people made fun of you. “Evening” went on until midnightand didn’t end until you said goodnight as you parted company.

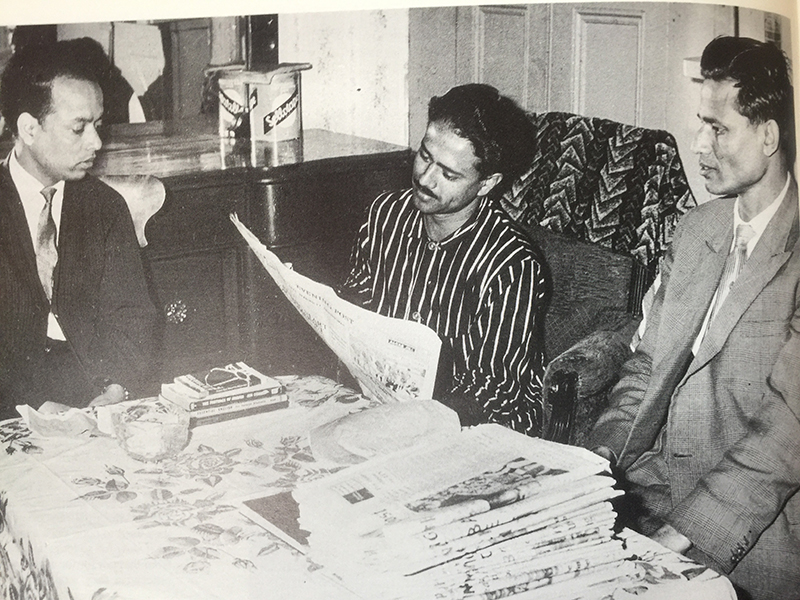

In Britain a new world was coming into being- on the seventh of April, the first regular Urdu weekly paper to appear in Britain, or indeed anywhere in the West—Mashriq—was launched.

When Mashriq was getting started, readers, thousands of miles from their homelands, were eager to hear every latest item of news from home. Most of them were people who before the appearance of Mashriq had never heard of any such thing as a newspaper. They came from those far-flung villages in their homeland where, if from time to time a letter came from some youngster who had emigrated, it was regarded as the common property of the whole village.

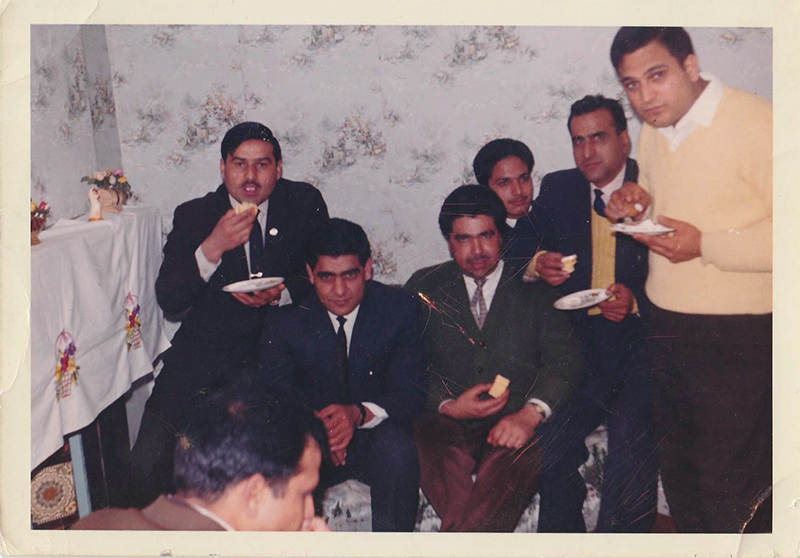

In those days, the new arrivals would work day and night in the factories and then on Sunday would gather at the house of anyone who had received a letter from his village. They would all listen to the letter—repeatedly—and then would spend their day off commenting on everything in it. When Mashriq appeared it was greeted eagerly, as though it too had come to them from their homeland.

When Mashriq came out the poets had a field day. It seemed as though all the “local” poets from Pakistan and India were now gracing Britain with their presence. Many of them began to send their ghazals and their poems- a couplet which made us surrender immediately. ‘They are false lovers who weep and sigh at night I spend the nights of separation from my love reading Mashriq’

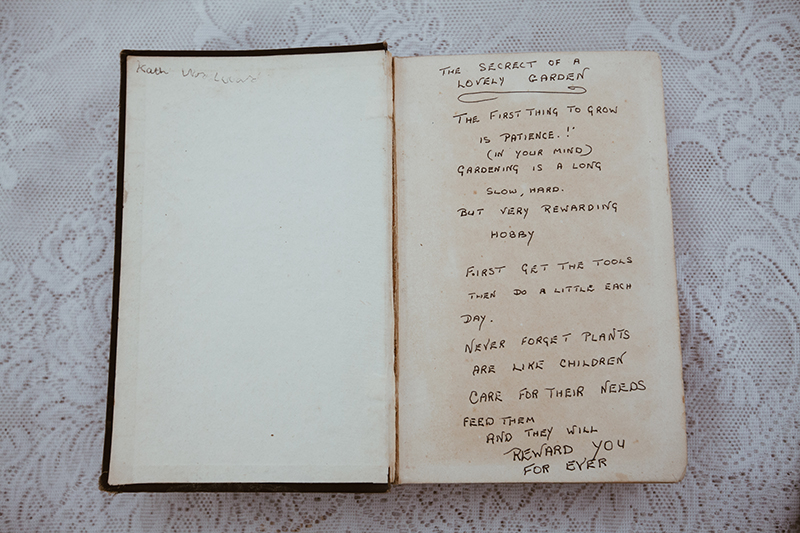

There were some readers of Mashriq—granted, not very many—who were absolutely illiterate. They would buy the paper and get somebody else to read it out to them, after which they would engage with great confidence in an exchange of ideas with their educated compatriots about politics and current affairs. Some of them became so accustomed to reading the paper that when after a year or two they would return to spend some time in their village they would make arrangements for Mashriq to be sent to them regularly while they were there. And there was no lack of readers who had read the Holy Qur’an in the village mosque and used their knowledge of the Arabic script to read the Urdu of Mashriq. It didn’t bother them if they couldn’t read every word written in it or understand what they had read. It was enough for them to feel that this was their paper and that since it had come into existence they were no longer “illiterate” or “uneducated.” In the icy mornings on the bus journey to their factory or during tea-break or dinner-break in the factory when their English mates were looking at their papers and studying the football pools, they too would take Mashriq out of their pocket and become engrossed in reading it. This was their own paper, the expression of their own language and their own culture. Before Mashriq was launched they would sit at such times not knowing what to do or talking to each other in their own language, and their English mates would regard them as backward, illiterate people. Some of them would look upon them with contempt. Others would feel some sympathy for them, pleased with themselves for showing the compassion which God-fearing people should. Some of them did not think them fit to be regarded as human beings. But now, when they saw Mashriq in their hands, they began to feel that these black and dark brown creatures too were human beings, people who like them had a language of their own and a language sufficiently developed to produce newspapers, and if these people did not know English then this was absolutely no justification for regarding them simply as animals who after a little practice could be harnessed to a machine to do physical labor. Now quite a number of them began to feel quite impressed. In Mashriq they acquired an identity and a sense of self respect which up until that time in this strange country had been totally lacking. Mashriq was the paper of illiterate people, of illiterate laborers, but these illiterates were often people who were better men than the so-called educated. They came to this new country, and when they encountered favorable conditions and opportunities to improve their life then their latent capacities became evident, and once having learnt the secret of confidence in themselves their personality began to develop in a new form.

As the paper became more and more popular the numbers of our organizations and associations in Britain began to increase and their scope began to extend. There were even meetings to arrange for demonstrations—a demonstration outside the Indian High Commission about the Kashmir question, demonstrations in front of the Pakistan High Commission about the extension of passports, protests against the policy of the High Commission, demonstrations outside Marlborough House on the occasion of the annual Commonwealth Conference. Reports of these meetings and of meetings of delegations of different organizations and associations with the Pakistan High Commissioner became more and more numerous. We reached a point where the pages of Mashriq proved to be inadequate to cover all these things.

In 1963 a law was passed restricting the entry of immigrants. Before that all you had needed to come here was a passport. Now in order to come you had first to get an entry certificate or a visa from the British government and this entry certificate was easier for the B.A.s and M.A.s to try their hand at getting than it was for the villagers of Mirpur and Panjab. And now came the time when not only were educated immigrants coming, but people began to send for their wives and children, and these wives and children began to arrive to join their husbands who had already come here. These newcomers began to appear upon the British scene, and we had to add to Mashriq a women’s page and an education page. The women’s page was written at different times by Rafat Iqbal and the wellknown short story writer Mohsina Jilani who had come to London with her journalist husband Asaf Jilani.

Mashriq, which up until that time had had 16 pages, eventually grew to 40 pages. The first Pakistani to be made Justice of the Peace in Britain was Muhammad Sabir, and on that occasion we printed his picture to cover the whole title-page. He had been a clerk in some railway office in Lahore before he came here and within a few years had been made Justice of the Peace in Manchester. Similarly in a Birmingham school Najma Hafiz was made “top girl” and we made this too our title-page story. After a year or two Muhammad Aslam, who had come here from Jatila Mirpur, qualified as a chartered accountant and became the second Asian Justice of the Peace in Britain, and we gave great prominence to this news as well. Quite soon the developments which led to Asians becoming Justices of the Peace and the award of various honors to Asian school children gathered such pace that news items of this kind lost their former importance. Now we began to print them on the page devoted to local news under the heading “Where We Are.” Gradually we had to increase the number of pages devoted to local news.

Through Mashriq we raised substantial sums to help the Muslims of Palestine and Cyprus. Then when it was planned to build a big mosque in Birmingham we raised something like £4,500 in contributions. In those days this was reckoned to be quite a large sum. In those same early years in Mashriq the movement for religious education which is now the norm in British Muslims’ life began.

Another poet whose verse used to be published in Mashriq in those days was Ustad Batangi. There is a couplet of his which many people in those days used to recite as expressing their own position: Here in a London mill I carry sacks And spend my weekly earnings on white girls.

I was with Mashriq for eleven years and four months. When I launched it it was a challenge, probably much the same sort of challenge which the discoverers of new worlds experienced after crossing the oceans. Work on it was a sort of obsession. I felt as though I was waging a very great campaign. Along with a few friends I worked from seven in the morning until eleven or half past eleven at night and never took a break at the weekend; and yet I never felt tired. We were all very happy. In the early days of Mashriq I enjoyed my work, but now we had entered a period of earning and paying out money and I often used to think, “If I have to give myself a headache, then why this headache?” I gave up the post of Chief Editor of Mashriq. The directors could not understand—and I myself could not explain it to them.