Memory Erased

By Nihal Farid

PAKISTAN PHOTO FESTIVAL FELLOWSHIP 2021 PROJECT

The surrender meant the loss of nearly half of Pakistan's territory after a war that lasted for just 13 days, and is one of the shortest wars in history.

On December 16, 1971, a civil war came to an abrupt and humiliating end with the surrender of nearly 90,000 trapped Pakistani soldiers cut off from supplies, communications and all roads back to their bases in West Pakistan. Not since the end of WWII had the world seen an army suffer such a sweeping defeat, one whose scars still mark the Pakistani social and political memory. The surrender meant the loss of nearly half of Pakistan’s territory after a war that lasted for just 13 days, and is one of the shortest wars in history.

As a young Pakistani citizen trying to explore my country’s history, I am faced with many questions. One of these is about the darkest chapter of Pakistan’s military history: the separation of East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.

This part of my country’s history remains largely erased from official, educational and private memory. And yet, it is a chapter that continues to make Pakistan’s policies towards its citizens, its territories, and even that of its conflict with India over Kashmir, etc.

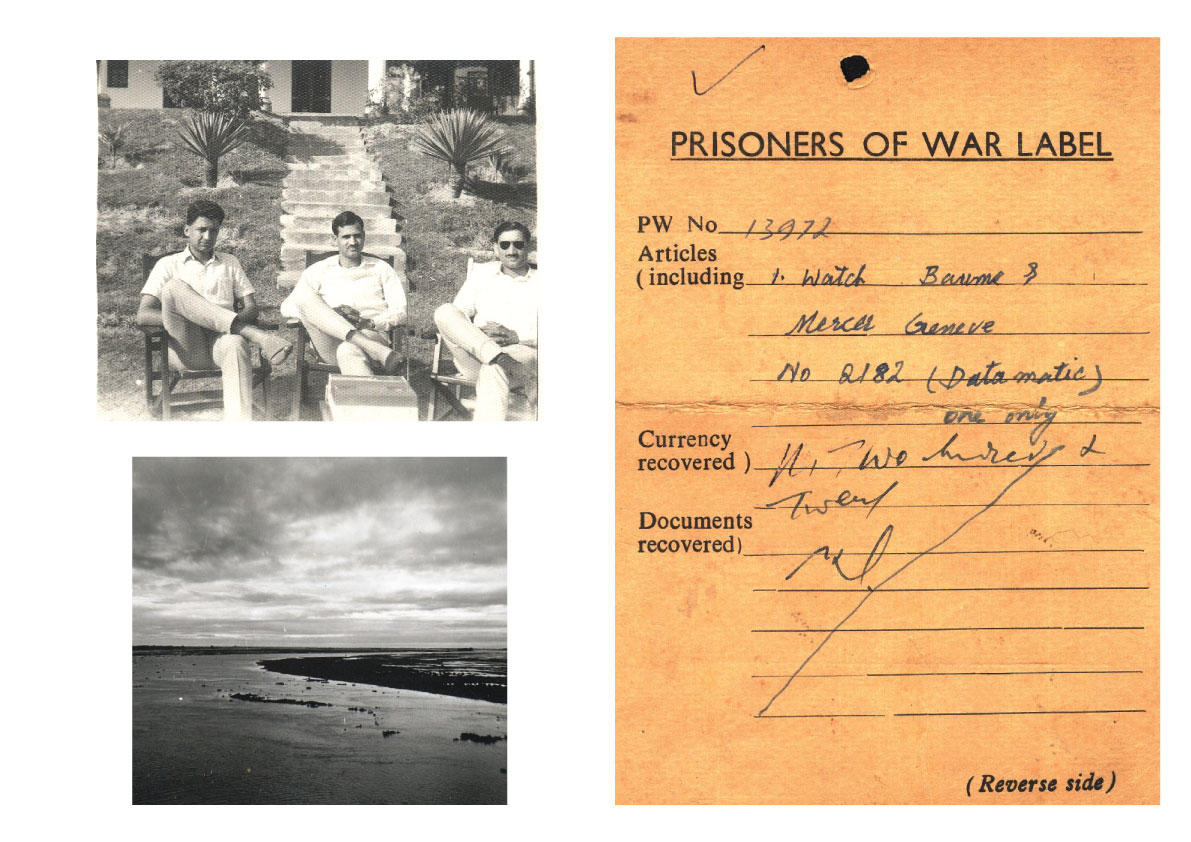

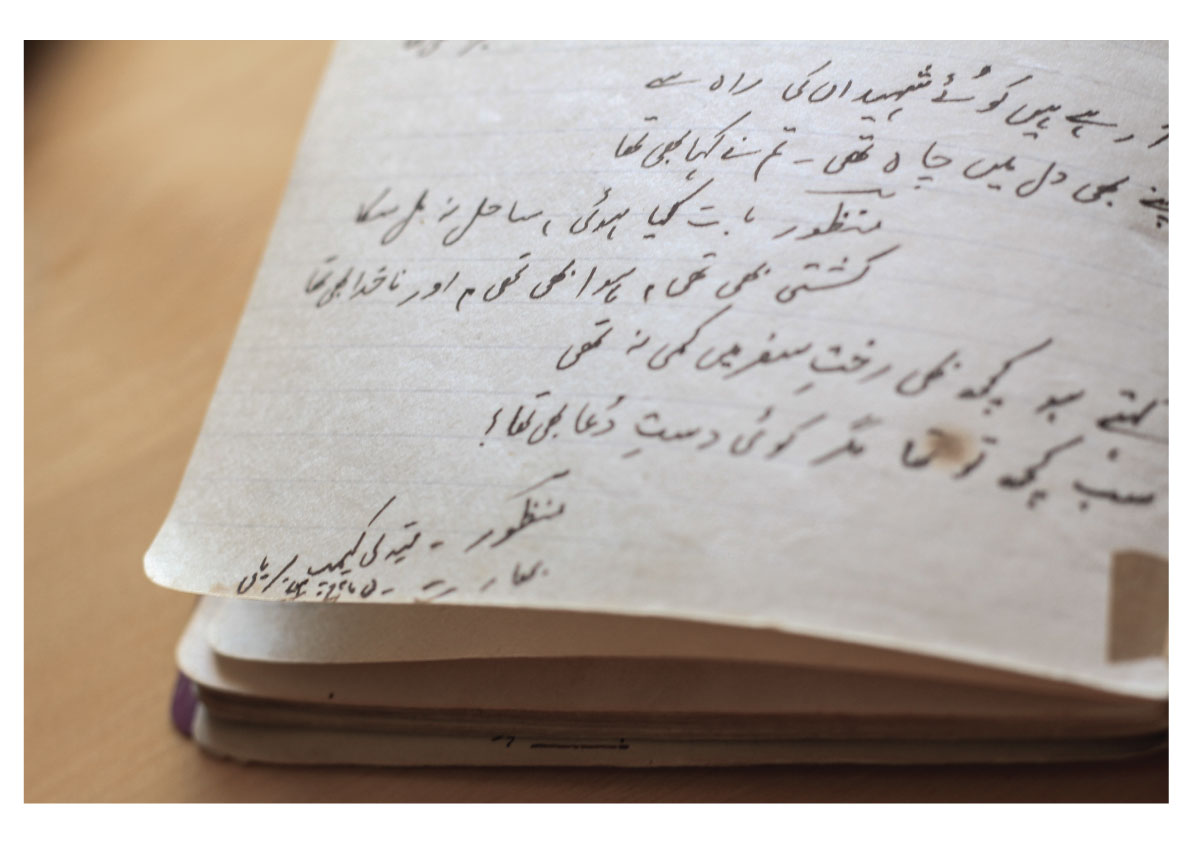

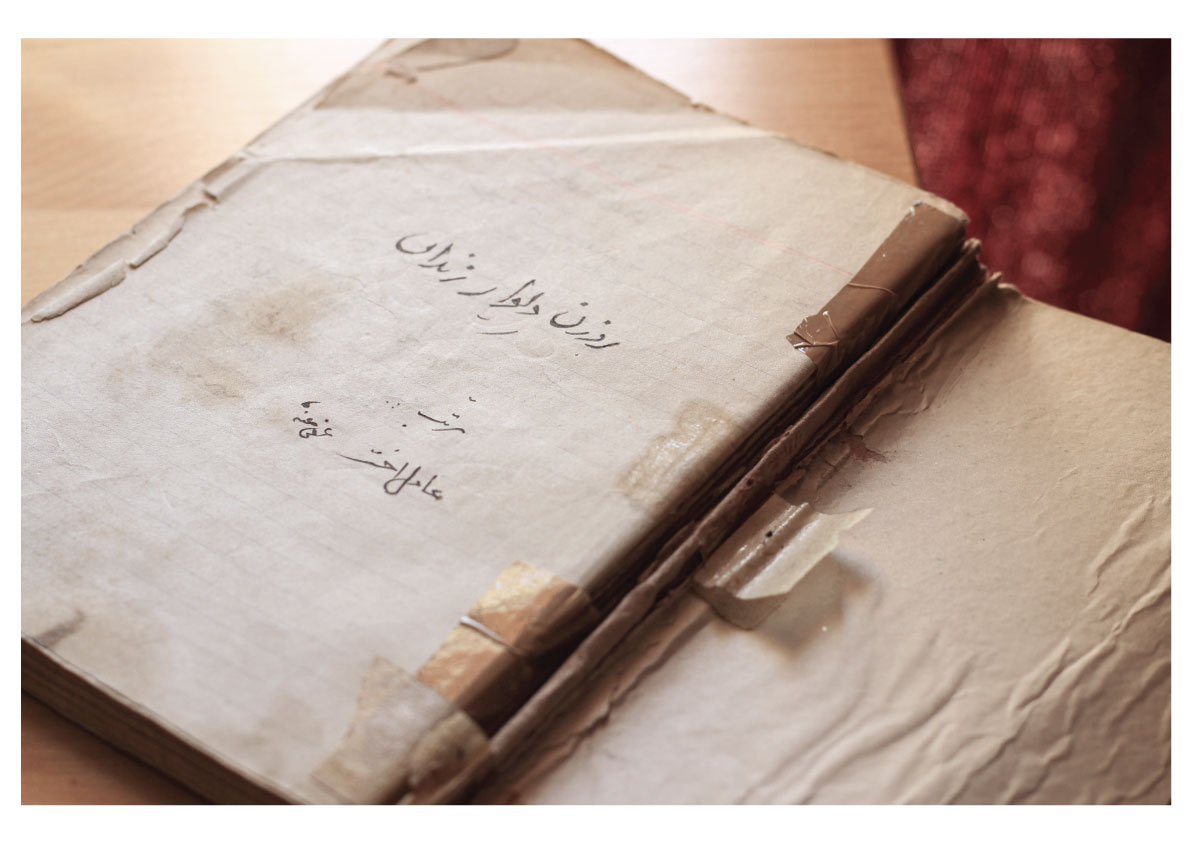

My project is an archeology of erased memory, as I attempt to understand what happened in 1971 through the memory and experiences of the men who were abandoned in 1971, and suffered two years of imprisonment as Prisoners of War (PoWs). This is a project about Pakistan, as much as it is a project about my late grandfather, who used to narrate stories to me over the dining table when I was a little girl.

Method

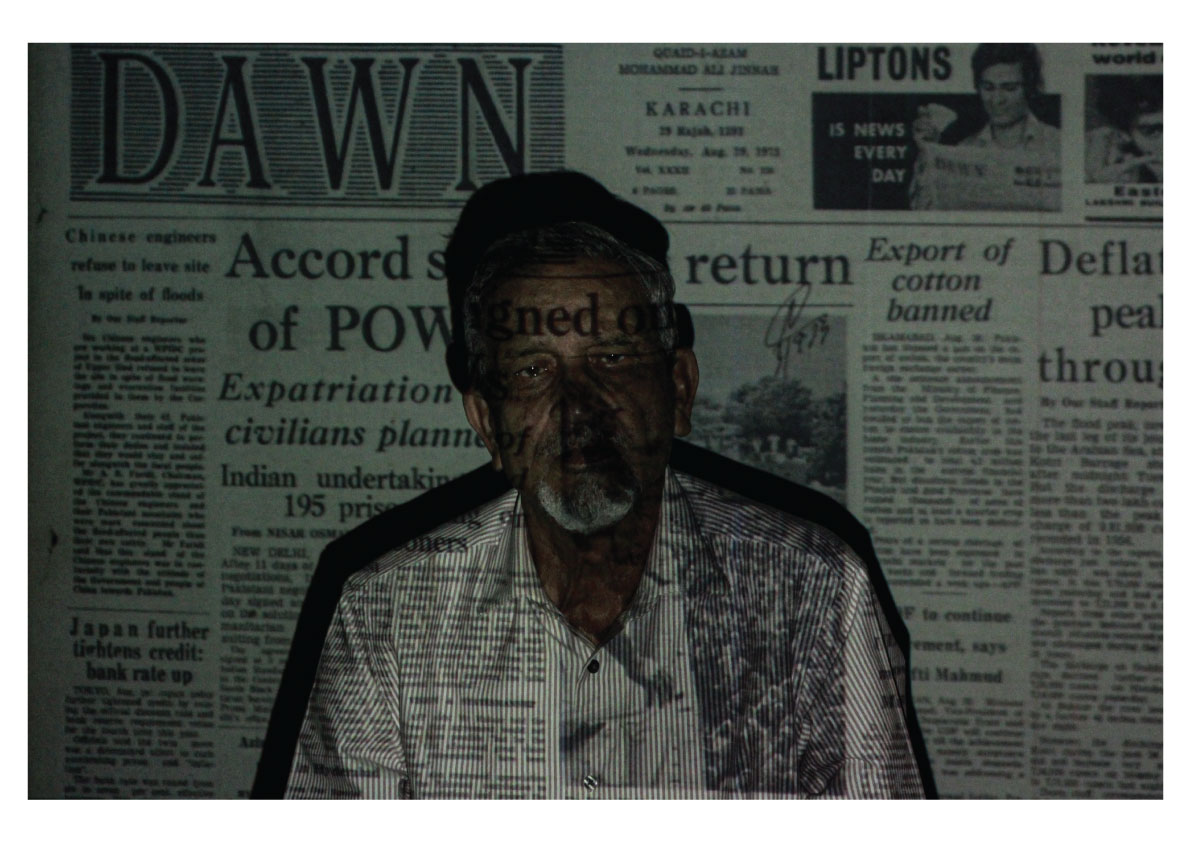

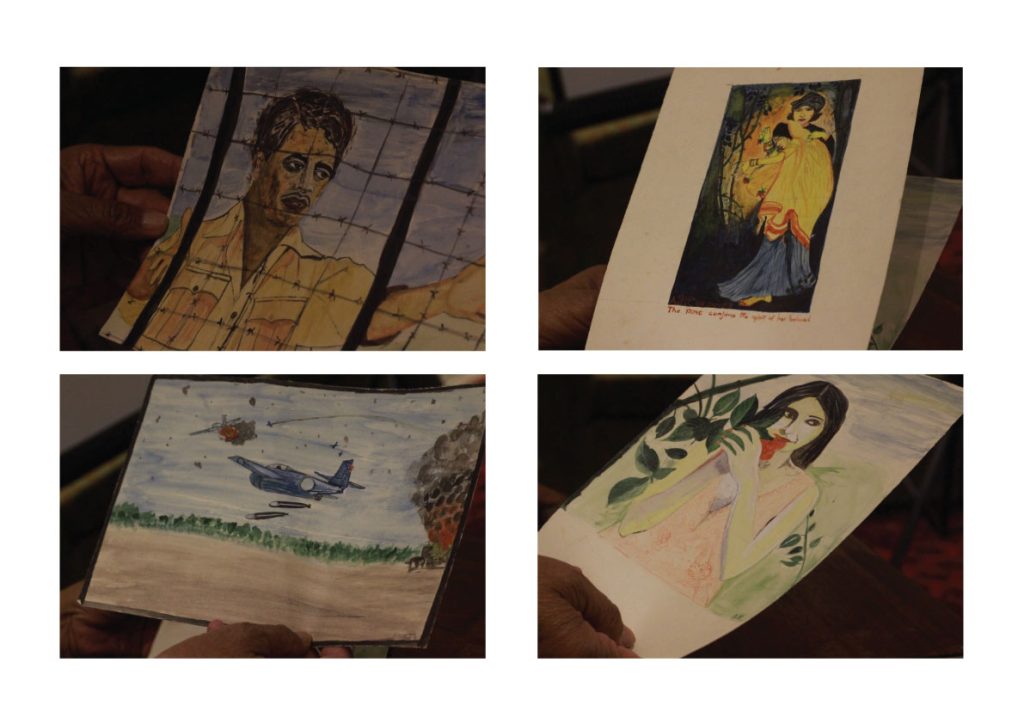

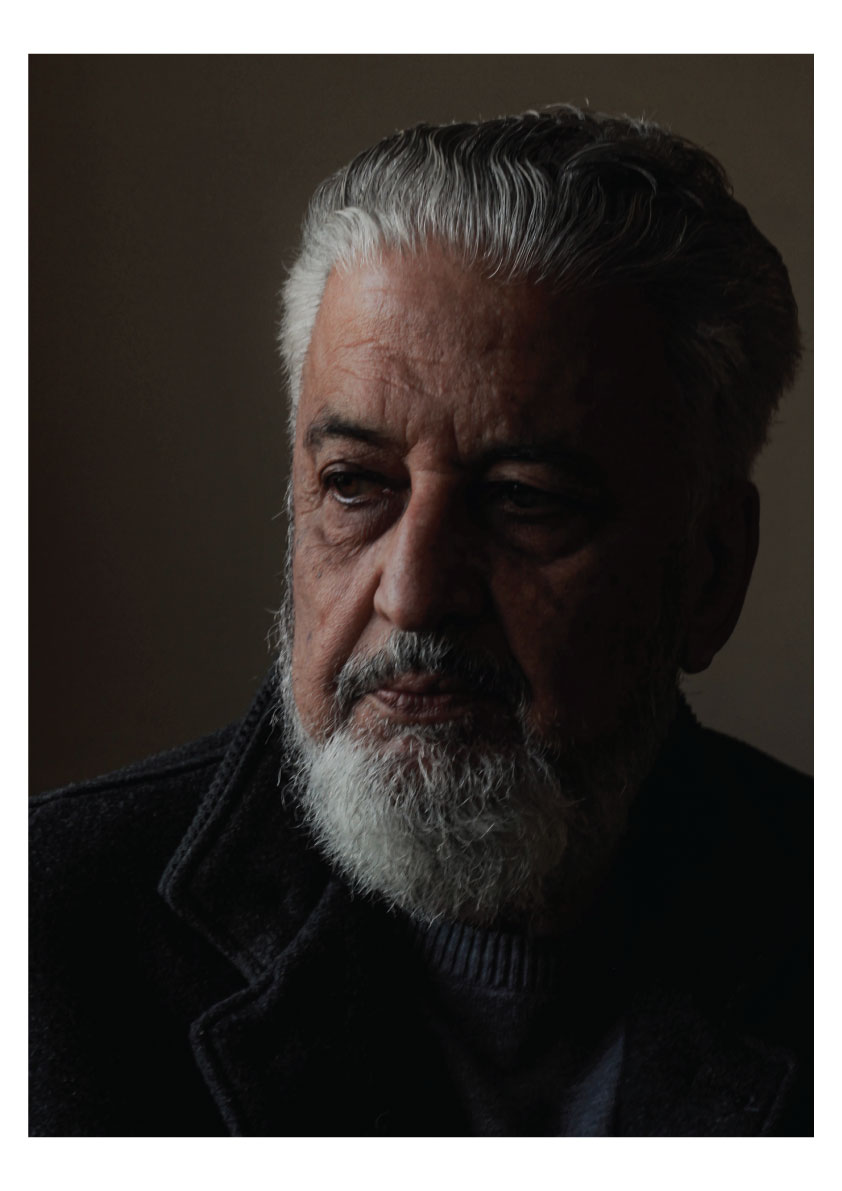

In the winter of 2021, I began meeting retired officers in Rawalpindi who became Prisoners of War after the fall of Dhaka I kept regular contact with four of them. They were detained in Camp no. 58 in Bareilly Cantt. 51 years later, these officers are still good friends. Some of their friends have died, others have frail health. I visited their homes, listened to their stories, and looked at precious archives. Multiple drawing room conversations later, I was able to experience flashbacks of their time in the camp. It’s my attempt to record their personal histories of trauma and survival. This is the last surviving generation that witnessed the 1971 war. Through their stories, I have been given a window to their past.

LT COL (R) ADIL AKHTAR: Memories from the camp

“When I became a prisoner, I was a young lieutenant, barely 22 years old. War is a horrible experience of a person’s life and after war, becoming a prisoner is an even more horrible experience. What I want to say is that even then I was under god’s protection. I had an able body. I had a perfect eyesight and loved reading. That’s what I did the most during camp. I arrived in the camp on 5th January 1972 and stayed until 1974.

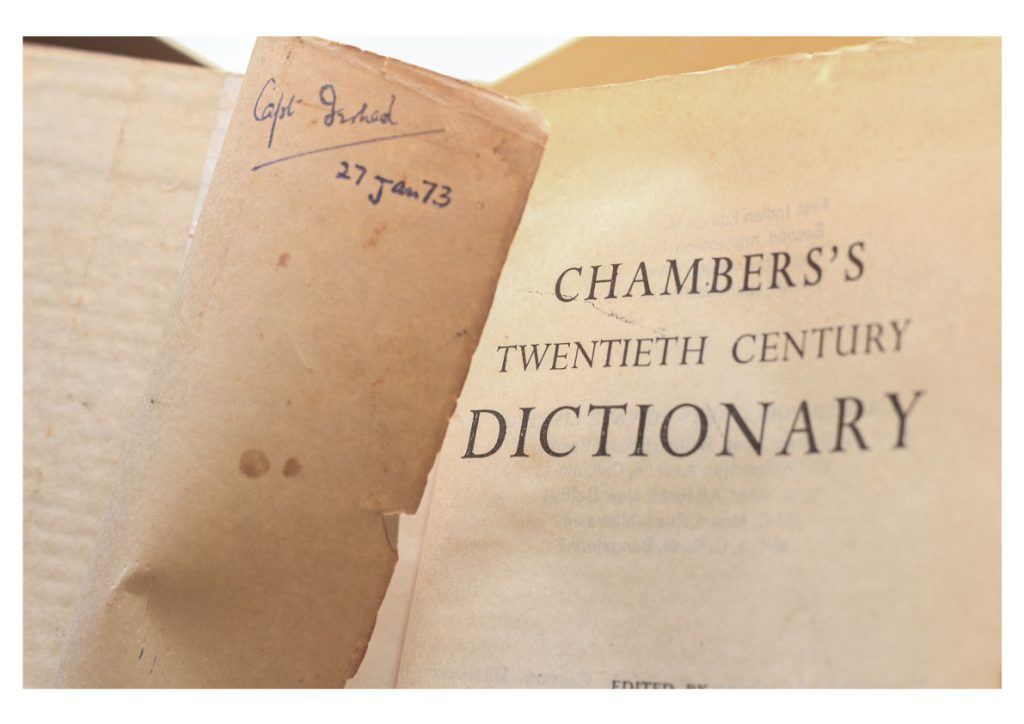

An Indian bookseller was given permission to visit camp to sell some classic titles. He visited our camp with thousands of books every 2 months. It was surprising that the books were very cheap.

After Red Cross assigned us some pocket money, we could buy things worth Rs. 92. We couldn’t use cash but we could buy things. I bought many titles in literature and military history. A reader wishes to have uninterrupted free time in life to read all the books he wishes. I found that time in camp. I read Tolstoy’s War and Peace. It had thousands of characters and I couldn’t remember all of them but not only did I read that novel, I found my intellectual horizon widen. Which aspect of Tolstoy has not been reflected in that book by Tolstoy? Hatred, love, envy, generosity, every emotion…. and so much more, you name it. I developed a lot of maturity. Years after coming back, I read it again and understood it better.

The other greatest novel I read was Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. A senior friend in camp told me that to read Dostoevsky, “Either you have to be mad already or you will become mad after.”

In the camp, the setting to read or write was extremely uncomfortable. 10-12 barracks with cone shaped roofs carried charpoys and the floor underneath was muddy. We used to read while sitting on the bed. After a while I got used to read while laying on bed with my pillow slightly turned up.

Our camp was a very desolate area. Bareilly was once a huge cultural and religious centre for Muslims. Barelvi sect of Muslims originate from there. I don’t know how the rest of the city looked like. The camp was ugly. All the barracks were surrounded by 3 layers of locks and a sentry dog used to roam all around. I saw 18 feet high towers of bamboo on top of which a sentry (watch guard) used to be on duty all the time. Flashlights and machine guns were installed on the top edge of the tower, which the sentry could rotate to see dark patches around our camp.

Repatriation:

“When it was time for us to be released after two and a half years, one day an Indian commander came with lists of 25 officers each. He assigned first 4 lists for the first train which was to take us back to home. It was hard for me to leave my friends behind. The first train left at 14 November. I got on the second train which left on 16 November, etc.”

They tied us all in a truck and took us to the Bareilly railway station. After we boarded the trains, the train was also locked up. The train kept moving all night.

Bareilly is located slightly east of Delhi. I remember passing by Rampur, Moradabad, East Punjab then Amritsar. The other morning, we were taken out in Amritsar. From there on, we walked about a kilometer and reached Wagah border.

Each soldier was counted and then handed over to Pakistani officials.

MAJ (R) MUMTAZ

During the tragic events of 1971, I was posted in East Pakistan and witnessed the blood-shed of innocent non-Bengalis by Mukti Bahini rebels. On the outbreak of armed Bengali insurrection in East Pakistan in March 1971, the port city of Chittagong had a sparse representation of non-Bengali regular troops. The hopeless troop’s ratio of Bengalis and non-Bengalis was 20:1.

I was serving as a Captain with 53 Brigade in Comilla. Upon the formation being assigned martial law duties in Chittagong and Chittagong Hill Tracts Districts, we moved and established martial law HQ at Circuit House, Chittagong.

The bloodshed:

The port city and its sub urbs remained at the mercy of Mukti Bahini rebels till the end of April. The rebels had put up stout resistance in different parts of the city. The period saw barbaric atrocities perpetrated on unarmed non-Bengali civilians. The Circuit House of Chittagong was used as a slaughterhouse by the rebels of East Bengal regiment. Chittagong Medical College students established a blood bank and stocked it by forcible bleeding of non-Bengali civilians.

On 15th April, our troops were engaged in a last ditch battle against rebels in Isphahani Jute Mills Complex on the river Karnaphuli bank, downtown Chittagong. I went to collect the details of dead bodies and found a shocking sight. Hundreds of non-Bengalis, mostly women and children, lay slain, The massacre happened a day earlier. The walls were riddled with bullets and fired empties were scattered all over. Disposal of dead bodies was an immediate task. Due to heat and dampness, the air was filled with foul odour. While passing by three storied residential apartment next to the Officers’ Club, I observed blood dripping, turning the stairs red, I went up to trace its trail along with two soldiers and reached the top floor which was bolted from inside. We knocked the main entrance door. There was no response, except some audible signs of life inside. When we struck the door with rifle butts, an injured lady opened it. Her 15 years old daughter was clenching her from behind.

The scene was simply awful. We found another 14 dead bodied of women and children. Besides the mother and daughter, there were four more survivors, all injured and traumatized.

The semi-conscious girl named Haseen had a bullet in her neck, and bayonet wounds in her belly. We evacuated all the victims to the Naval Hospital. This incident left indelible imprints on my mind.

In August 1971 I was posted on promotion to 3 Punjab located in Sylhet. After the fall of Dhaka I remained captive in India till November 1973. In 1977-78, while serving at Karachi, I tried to locate that little injured teenager and her mother but my efforts bore no fruit. I had to wait for nearly 49 years to rediscover that wounded little teenager (now Mrs Haseen Durrani) whose sobs and cries have been haunting me since that heinous crime. Mrs. Durrani and her mother were amongst the six survivors of the carnage. She is a former teacher and grandmother leading a retired life in Karachi. Her mother passed away in 1990. A friend in Karachi got me in touch with her.

Lt Shamsher of EBR who was the mastermind of this massacre was subsequently captured by 24 FF while fleeing from HMC. He confessed not only to the brutal killings in IIJMC, but also to having raped several dozen non-Bengali girls, to satiate his brutal appetite for vengeance.

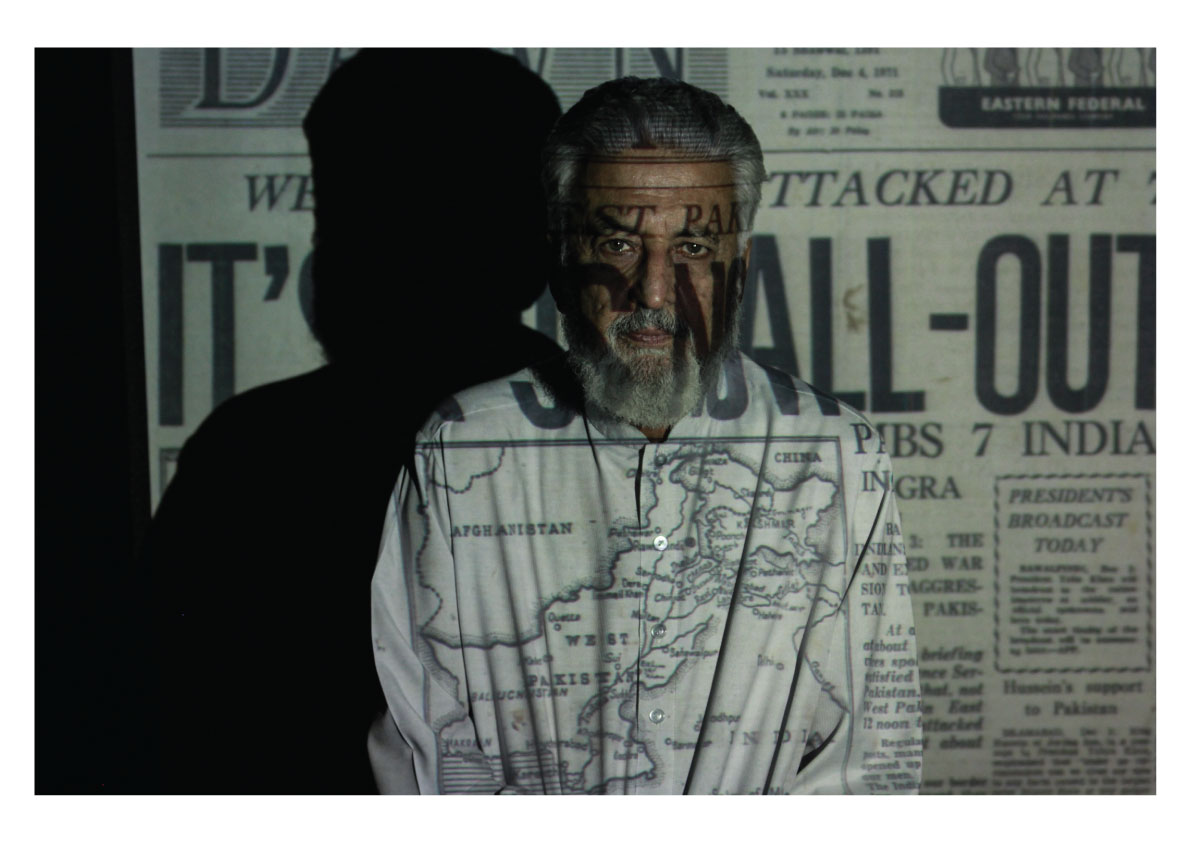

BRIG (R) IRSHAD

East Pakistan was a semi-mountainous terrain. It had many rivers, and cyclones were a frequent occurrence. I went to Dhaka first in July 1970. When the insurgency broke out, I was deployed as G3 Intelligence in Raachai. Every day, we were losing 1 officer, 3 JCOs, 30 ORs on average. As per my calculation, 50% of officers were martyred before war started. The infantry fought without its usual combat support/complements.

When Dhaka university bus was arrested, I was with Intelligence. I went through the preliminary interrogation report in which one student, who had successfully reached India to save his life, said that the military action took away his father. “I don’t know where my sister and brother is. I will kill 10 of you out of revenge.”

The Camp:

The first train carried 195 criminals. When we were taken there, we were shocked to see that they had properly arranged camps all ready. There were 2 rooms in every barrack, and in every room, there were 14-15 beds. Multiple locks were kept in place: room lock, barrack lock, camp lock.

There used to be a big trench for use as toilet. The trench was covered with wooden planks which had a covering made of Hessian cloth on top of it. After 3 months, those toilets were closed and CGI sheet washrooms were created. Officers used to wait in line every morning.

Every time there was a power outage, headlights of 5-6 military vehicles were turned on. In case main line turned off, Automatic generators were made operational. Bunkers near fence.

The battalion looking after security was replaced every 3 months. In the case of any untoward incident, surprise search used to be done.

COL. DR. INAYAT

“I was a little luckier than other people because I could frequently see life outside the camp. That was because I was a doctor and was taken out to treat PoWs of all camps located in Bareilly. I treated a few soldiers who were injured while escaping through tunnels.

I still remember the ambulance driver who used to pick me and drive me outside. When Eid day approached, he asked if we wanted something to eat. The next day he brought Kachori (deep fried dough balls).”